by James Cave

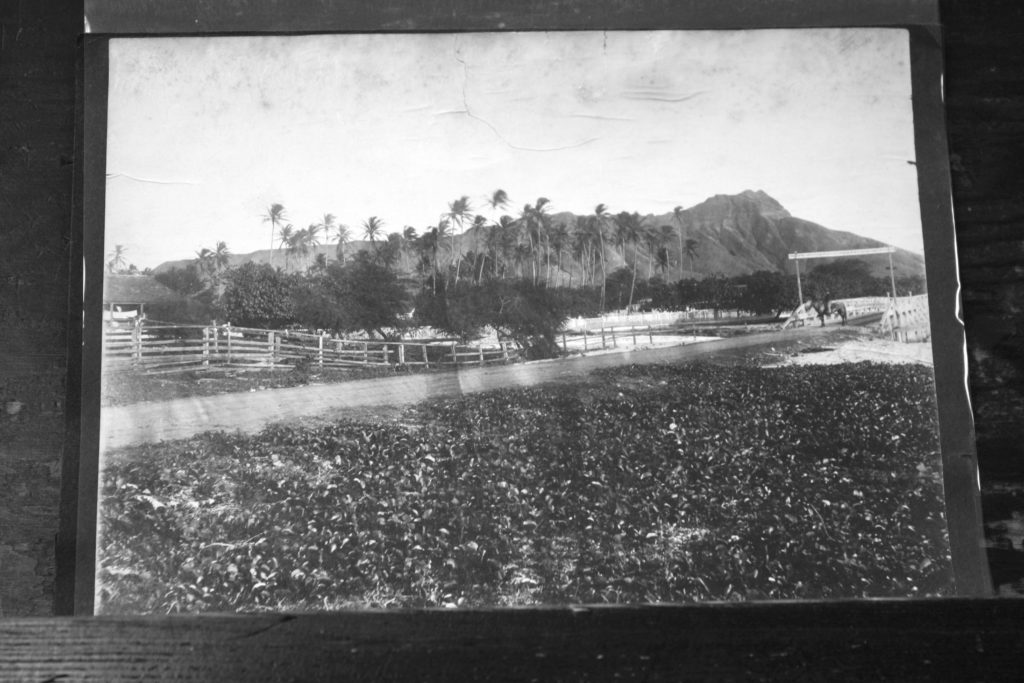

Waikiki in the 1800s: It was a soggy, mosquito-laden marshland of fishponds, taro patches and coconut groves. It was not the solid ground fit for skyscrapers and resorts that we know it for today. All that would come later. Early Waikiki, for the native Hawaiians and the Polynesian explorers before them, was revered for its healing waters, or kawehewehe— a Hawaiian word that translates to “the opening up.”

Today, Waikiki is the heart and soul of Hawai‘i’s tourism industry, a Vegas in the Pacific responsible for 21 percent of

Hawai‘i’s entire economy. But the earliest inhabitants of this beautiful, isolated paradise long understood this stretch of southern shoreline’s aesthetic and spiritual value — as long as humans have bore witness to it, Waikiki has been the place to be.

And so it was for Robert Lewers, an early Honolulu lumber merchant and philanthropist who built a two-story home on Gray’s Beach in 1838. “Uncle Robert,” as he was known, was a “link for years between that glamorous early Hawai‘i with its monarchial pomp and court ceremony and the thriving business community Hawai‘i became under American jurisdiction,” wrote the Honolulu Star-Bulletin at his death in 1924. He didn’t care about the political affairs of the land or the overthrow of the Hawaiian monarchy in 1893, he cared about business and family.

of marshlands; Prince Jonah Kuhio Kalanianaole, Jonah Kuhio, 1871-1922

Lewers soon offered the house to fishermen to dock and rest, and in 1907, leased it to local journalist, Edward Irwin, who officially considered it the Hau Tree hotel—it consisted of the beachfront home and five bungalows (21 rooms for about 40 people). When that lease expired 10 years later, Juliet and Clifford Kimball took it over and gave it a name, but the locals had already done that years before: They called it Halekulani, or “house befitting heaven.”

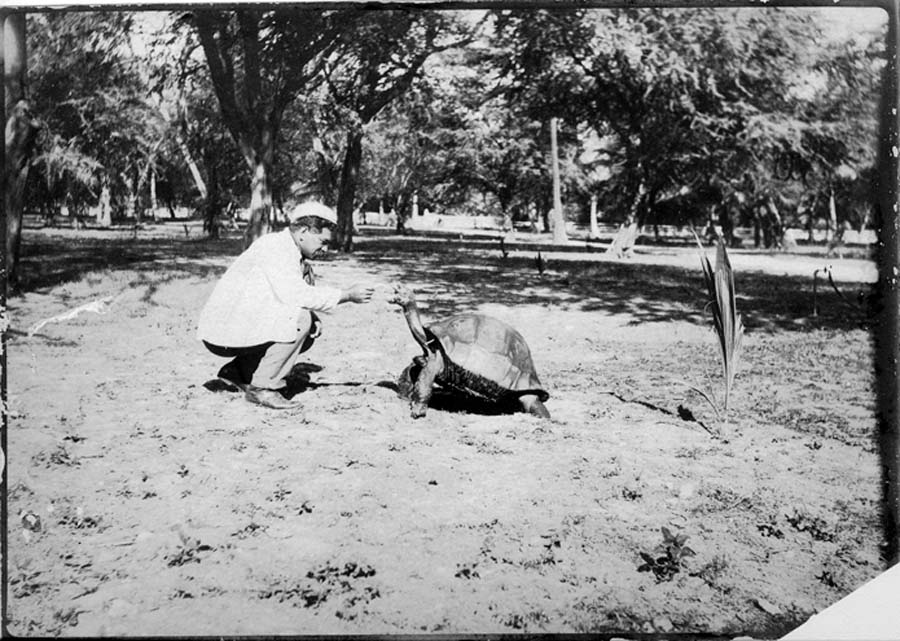

Back then, amidst the duck ponds and solitude (after all, Waikiki was four miles away from the sea-port of Honolulu and its bustling whalers harbor), visitors would ride the train into Waikiki and get off near their hotels, or perhaps they brought their own Model T—mainland visitors sailed to Hawai‘i on giant luxury ocean liners, sometimes bringing along their own cars and staff. One wonders what the Granthams of “Downton Abbey” would have thought if they ever traveled as far west as Hawai‘i; chances are they would have stayed at Halekulani.

It was also in the ’20s when Earl Derr Biggers stayed (and then was stranded during WWI) at the house next to Halekulani, when it was called Gray’s Hotel. There, he wrote the book that would introduce the Honolulu detective Charlie Chan to the world, House Without A Key, which was first published in 1925.

By the ’30s, the Kimballs had established a solid reputation as having a fine hotel in a beautiful land.

They’d expanded by acquiring the adjacent Gray’s-By-The-Sea and the Arthur Brown home (where present-day House Without A Key is now), but even paradise couldn’t escape the long, shriveling reach of the Great Depression.

In the late ’30s, Hawai‘i was dependent on the money spent from mainland visitors, much like it is today. If the mainland was hard for cash, so was Hawai‘i. But wealthy travelers, made of old money, still came across the seas, and Halekulani’s reputation of providing the finest service reached deep into those circles of society and carried it through into, well, at least until war hit the islands a few years later.

What were once festive streets filled with wide-eyed, weary and sunburned tourists before December 7 quickly became darkened under martial law every night within five months after the attacks on Pearl Harbor. Photographs in a May 1942 issue of Life Magazine show the once-glistening Aloha Tower extinguished under the nightly blackout.

Wartime in Hawai‘i immediately brought with it years of martial law, curfews and tire rations; beaches were fenced in barbed wire for fear of invasion from the sea. Sandbags were piled in front of important buildings, such as Honolulu City Hall, and residents were required all to wear gas masks (even the keiki at school). Anyone who broke the law would be tried in military court, and fines could be paid in blood to the Red Cross.

The influx of military personnel to an island not